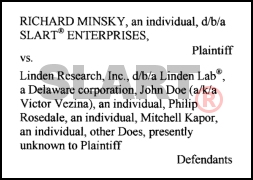

There’s an interesting post over at Not Possible In Real Life asking the question: “What is the correct (and legal) way to attribute photography and video shot in virtual worlds?” I was going to leave a comment there, but there’s really no way to answer this question off the cuff, so I’m turning it into a post instead. You should definitely visit the post at NPIRL too, particularly for the ethics of the situation; I’ll focus on the legal questions here. The bottom line? At least under the law as it currently stands, in-world shutterbugs need to be very careful — more careful than they would be in real life.

Here’s the setup. In a virtual world like Second Life, users have the ability to create things (like buildings, clothing, avatar appearances, and more) and the users retain intellectual property rights in these creations. Users can also take screenshots of this world, including these creations. So one user makes a 3D building in a public part of the world using the world’s creation tools, and then she logs off. The building, of course, stays in the world, since that’s the whole point of persistent spaces. Later, another user comes along and takes a screenshot of that building with a model-avatar standing in front of it. The model is wearing a red dress, a complex hairstyle, and a “skin,” all from different content creators.

Here’s the setup. In a virtual world like Second Life, users have the ability to create things (like buildings, clothing, avatar appearances, and more) and the users retain intellectual property rights in these creations. Users can also take screenshots of this world, including these creations. So one user makes a 3D building in a public part of the world using the world’s creation tools, and then she logs off. The building, of course, stays in the world, since that’s the whole point of persistent spaces. Later, another user comes along and takes a screenshot of that building with a model-avatar standing in front of it. The model is wearing a red dress, a complex hairstyle, and a “skin,” all from different content creators.

So that’s our picture. An avatar wearing a virtual red dress standing in front of a cool building in a virtual world. The questions are:

- What rights do the users who created the building, the model’s skin, the model’s hairstyle, and the model’s dress have in their creations?

- What rights does the screenshot-taker have?

- What obligations does the screenshot-taker have to the creators of the building, the skin, the hairstyle, and the outfit?

Copyright Law and Real Life Creations

It’s awfully tempting to drop back to real life for an answer. After all, the virtual world looks a lot like the real one. And in real life, photographers can take pictures of many (though not all) things without worrying about a copyright lawsuit. The problem is, that may not translate to the virtual world. We have to take a look at what copyright law actually protects to see why.

Copyright protects “original works of authorship including literary, dramatic, musical, and artistic works, such as poetry, novels, movies, songs, computer software, and architecture” that are “fixed in a tangible form of expression.”

So in real life, copyright law generally prohibits a photograph of a model sitting on the Spoonbridge and Cherry sculpture, a model embedded in a film cell from Titanic, or a model posing with poster-sized blowups of pages of text from my book, Virtual Law. But the scene with the model in a red dress in front of a building on a public street? In real life, that’s probably just fine.

That’s because copyright law generally does not protect real-world clothing (because it is deemed a “useful article“) nor does it protect hairstyles and makeup (because they are not “fixed in a tangible form of expression”). And though copyright law does protect architecture (at least for plans for and designs of buildings constructed after December 1, 1990), taking pictures of and creating artistic works using buildings that are ordinarily visible from public places is specifically allowed. These limitations on copyright law may not mean much in the virtual world, however.

Copyright Law and Virtual World Creations

The problem with applying real world copyright law concepts here is that virtual dresses, hairstyles, personal appearances, and buildings are not exactly the same as real world dresses, hairstyles, personal appearances, and buildings.

Real world hairstyles and various components of individual appearances are generally not protected by copyright because they either are not enumerated in the code, because they are not “fixed in a tangible medium,” or, regarding certain personal appearance attributes, because they do not represent “creative works.” Dresses and other clothing designs are not protected because they are “useful articles” and copyright law only protects “creative works.”  Buildings have special rules that protect their designs, but these rules do not protect them from photography or other artistic interpretation when they can be viewed from public places.

Buildings have special rules that protect their designs, but these rules do not protect them from photography or other artistic interpretation when they can be viewed from public places.

In the virtual world, however, every dress, hairstyle, avatar “skin,” and building is really a tiny piece of online software, and online software, including the output of the software to the screen, is protected by copyright. There’s even a copyright office circular (.pdf) describing how to go about registering the copyright in what the office describes as “works accessed via network (websites, homepages, and FTP sites) and files and documents transmitted and/or downloaded via network.”

The Debate

If I’m a content creator, I’m going to argue that when I am making something in Second Life, I am functionally writing code using the graphical interface Linden Lab provides me, and that code should be protected. Alternatively, I’m making digital art using tools that are only trivially different than those in a program like Maya or Blender. For some creations (such as virtual world animation packages that cause certain expressions and sounds) the code is obvious; the scripts are written in a formal scripting language. For others, such as buildings, the code is relatively hidden, but there is a good argument that building a skyscraper in Second Life is just “coding” one using a graphical user interface that operates as an overlay on the code, or that it is, at minimum, no different than any other creative work made using software. Certainly, no one disputes that artistic creations built using software (such as most of the second Star Wars trilogy) are protected works.

On the other hand, if I’m a virtual world photographer, I’m going to argue that there’s a real-life parallel here, and that buildings, personal appearances, clothing, and other objects in a virtual world should not be protected to any greater degree than they are in the real world.

Conclusions

With the caveat that no case has directly addressed this, I believe that the “code” argument will carry the day because it is simpler, it preserves the public policy arguments behind the real-world exceptions, and mainly, because holding  otherwise would undermine the now fairly well-established body of software copyright law.

otherwise would undermine the now fairly well-established body of software copyright law.

Many of the comments following the post on this at NPIRL that got me thinking about this in the first place speculate about just how much attribution is necessary when incorporating other people’s work into one’s derivative creations, but I think that the question is largely irrelevant. If you want to incorporate somebody else’s artistic work into your own you are supposed to seek permission from the copyright holder. And if you don’t, the copyright holder can sue you — attribution, no matter how extensive, is simply not enough.

Brad Templeton, Chairman of the Board of the Electronic Frontier Foundation covers this in a post entitled “10 Big Myths About Copyright Explained”.

U.S. Copyright law is quite explicit that the making of what are called “derivative works” — works based or derived from another copyrighted work — is the exclusive province of the owner of the original work. This is true even though the making of these new works is a highly creative process.

There are exceptions to this, of course, which generally get lumped together in the catch-all concept of “fair use.” These include criticism (which I’d argue covers my use of screenshots of in-world scenes in this article) and parody. The scope of fair use is beyond this article, but for readers who are interested in learning more, the Wikipedia entry on fair use is a good place to start, particularly the list of common misunderstandings of fair use.

This all means that with the exception of limited situations where fair use exceptions apply, I am pretty comfortable concluding that under the law as it stands, selling or otherwise making available derivative works comprising images shot in Second Life of other people’s creations, in most cases, does not qualify for fair use protection and is actionable as copyright infringement.

The easiest way for a content owner to deal with potential infringement is probably via the Digital Millenium Copyright Act (DMCA) policy of the site where content is hosted. For a private site, that’s probably the site’s web host, and for third party content hosting sites like Flickr and YouTube, the site provider itself typically offers DMCA takedown procedures. Linden Lab, of course, has a DMCA policy that would apply to in-world objects in the event that a creator wanted to have in-world screenshots removed.

Finally, I must stress again that this issue has not come directly before a court. Some argue that the law should be changed, and that could happen. The 2D internet has already challenged the bounds of copyright law, and the 3D internet is bound to take that debate in entirely new directions. This is one of those interesting areas where there could actually be new law created to apply to virtual spaces, or where established law might be interpreted in a non-traditional way.

For now, though? Virtual world content creators — from virtual dressmakers to virtual architects — enjoy protection from virtual photographers creating derivative works based on screenshots of their creations that exceeds the protection afforded their real-life counterparts.

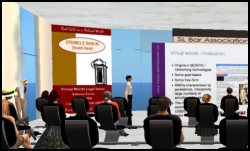

As part of the SL Bar Association’s speaker series, Kate Fitz (Second Life’s ‘Cat Galeilo’), is presenting “Web 2.0 for Lawyers” in Second Life Saturday, November 22 at 12:00 Noon Pacific time. Fitz, who is a public law librarian in Sacramento, California and member of the California bar, serves as the SLBA’s Vice President of Communications. She also runs the Lawspot Virtual Worlds Law Library. Fitz previously presented a well-attended and informative SL Bar Association seminar on online research tools for attorneys.

As part of the SL Bar Association’s speaker series, Kate Fitz (Second Life’s ‘Cat Galeilo’), is presenting “Web 2.0 for Lawyers” in Second Life Saturday, November 22 at 12:00 Noon Pacific time. Fitz, who is a public law librarian in Sacramento, California and member of the California bar, serves as the SLBA’s Vice President of Communications. She also runs the Lawspot Virtual Worlds Law Library. Fitz previously presented a well-attended and informative SL Bar Association seminar on online research tools for attorneys. You can sign up for a free spot at the seminar and also sign up and pay for CLE credit at the SL Bar Association’s site. Attendees who want CLE credit can pay for it via PayPal or in-world in Second Life, using Linden Dollars.

You can sign up for a free spot at the seminar and also sign up and pay for CLE credit at the SL Bar Association’s site. Attendees who want CLE credit can pay for it via PayPal or in-world in Second Life, using Linden Dollars.

The Polska Republika has launched as the newest self-governance project in Second Life. Here’s the

The Polska Republika has launched as the newest self-governance project in Second Life. Here’s the